Lessons for Labor & Community: A Century of Power Ebb and Flow in Appalachia’s Coalfields

As labor celebrates wins in sectors and areas all over the United States, this essay is a crash-course overview of power dynamics in West Virginia’s coalfields for readers in West Virginia and beyond.

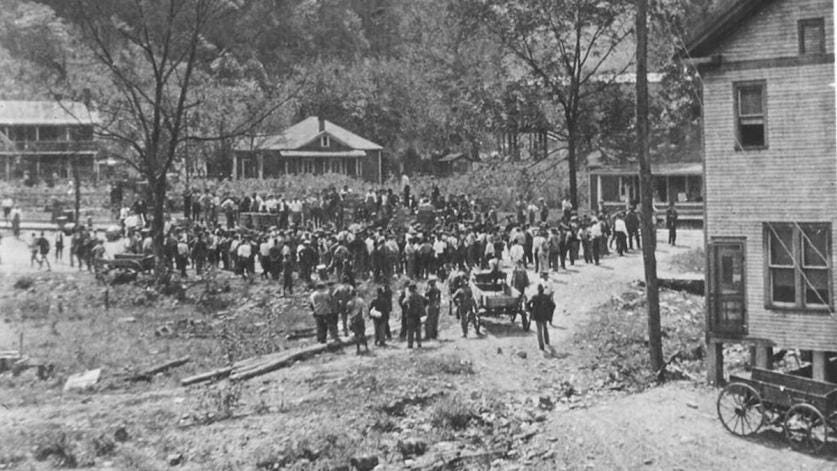

This year 2022 marks 101 years since the Battle of Blair Mountain and the culmination of West Virginia’s “Mine Wars”. And as of this publication in May 2022, the U.S. labor movement is organizing and building power at a level unseen in my lifetime. As labor celebrates wins in sectors and areas all over the United States, this essay is a crash-course overview of power dynamics in West Virginia’s coalfields for readers and organizers in West Virginia and beyond. This essay was originally submitted as part of my coursework in Appalachian Studies at Shepherd University and in response to a prompt to describe how the Battle of Blair Mountain was a pyrrhic victory for mine owners, coal operators, and colluding politicians in West Virginia. For organizers it may be an important history to understand, as history does not necessarily repeat, but it frequently rhymes with itself.

“A snake with its head cut off can still bite you” warns mill owner Richard McAdams in Wiley Cash’s novel The Last Ballad. Cash’s novel is specifically about the textile industry in North Carolina, but the lesson about decapitated snakes is one that mine operators and coal owners also learned in the years following the Battle of Blair Mountain, and one that organizers today can also learn from. While the operators and owners and the colluding politicians in the state of West Virginia all ostensibly “won” the Battle of Blair Mountain, the century-long history that has followed the Battle of Blair Mountain makes clear that the victory was short-lived and ultimately pyrrhic. The aftermath of the Battle for Blair Mountain and the union drives in West Virginia has so far unfolded in two broad stages: the first period was during the 1930s and 1940s, in which the unions gained strength and material wins; the second period has unfolded since the 1950s, in which the companies replaced labor intensive underground mining with capital intensive surface mining.

The Battle for Blair Mountain ended with around six hundred miners arrested and the union temporarily hobbled in West Virginia’s southern coalfields. Within two decades though, the miners had won nearly every concession that they had fought for during the Mine Wars. One factor behind the coal industry capitulating was the end of World War One and the onset of the Great Depression. Coal demand plummeted after the end of World War One, and the inherent instability of the coal industry was exposed further by the onset of the Great Depression. While the Great Depression is hardly referred to as a positive in American history, it did provide opportunity for union organizers such as John L. Lewis:

Lewis owed his opportunity during the 1930s to friendly federal legislation sponsored by [President Franklin] Roosevelt and his liberal allies. ‘The President wants you to join the union,’ UMWA organizers told the miners, and once again the union rolls swelled to record numbers. Coal industry leaders, in Appalachia as elsewhere, caught momentarily off balance and willing to try anything to alleviate the industry’s desperate situation in 1933, at first submitted tamely to Lewis’s whirlwind organizing campaign. (Williams 279)

The organizing drive continued unabated with UMWA Districts 19 and 20 signing up nearly 85 percent of potential members in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Alabama. Meanwhile in West Virginia, Williams reports that “total West Virginia union membership rose from a few thousand in 1931 to nearly 300,000 a decade later.” The Great Depression provided labor with a strong bargaining position and by 1934, “the UMWA signed the first of a series of industrywide contracts known as Appalachian Agreements, which, among other features provided for the gradual narrowing and then the elimination of the regional wage differentials” (Williams 280).

The Appalachian Agreements represented a huge victory that miners in West Virginia had been fighting for since the late 19th century; William C. Blizzard notes in When Miner’s March that “from 1898 to 1912 West Virginia increased its coal production by 350 percent – and still the UMW had been unable to organize the miners, despite their apparent willingness” (45). With union recognition and the narrowing of wage differentials, the coal companies in Appalachian coalfields had lost much of their competitive advantage that they had held over non-Appalachian coal companies: namely, a cheap, non-union workforce. At this stage in history, the Battle of Blair Mountain is readily seen as a pyrrhic victory for owners, operators, and colluding state politicians.

In the documentary Blood on the Mountain, AFL-CIO president Richard Trumka explains how companies had always treated workers as disposable, “If you killed a man you were okay, if you killed a mule, you got fired 'cus they had to buy mules—men were free. Human life was never given the proper priority.” This mentality of capital investments being valued greater than labor investments shaped the coal industry after World War Two and through until today. In the 1930s and 40s, the unions ultimately won the concessions that they fought for during the Battle for Blair Mountain, but in the fifty years that followed the “Appalachian Agreements”, companies aggressively replaced workers with machines. James A. Haught described the process in a 2017 article in the Beckley Register-Herald:

In the 1950s, coal owners began replacing human miners with digging machines, and misery followed. Around 70,000 West Virginia miners lost their jobs and fled north via the “hillbilly highway” to Akron and Cleveland. But coal production remained high.

In the 1970s, longwall machines could produce 10 times as much coal with half as many workers. And more jobs vanished because mining switched to huge surface pits, where monster machines and explosives do the work. The number of West Virginia miners continued falling — to the 30,000s in the 1990s, then below 20,000 in the new 21st century. Official state figures put today’s total around 12,000. The number of operating mines fell drastically. (Haught, “A Short History of Mining”)

The process of automation destroyed the unions and put power squarely back into the hands of coal owners and operators and the allies in state government. Over the course of the Appalachian history since World War Two, the coal industry has further entrenched itself as an economic driver in Appalachia, but the gains are even more disproportionately won by the industry.

On the one hand, the Battle for Blair Mountain was a pyrrhic victory for the companies, as coal miners won their concessions in the decades that followed the Battle, in part because public sympathies and public policy shifted to favor labor in the United States during the Great Depression. But that is only one-third of history’s postscript for the Battle of Blair Mountain. In the second part of the postscript, the companies turned toward capital investments and heavy machinery, opting to automate the coalfields rather than see company profits decrease.

And in the 21st century, we are now in a third phase of the coalfield power struggle, with communities fighting for economic development beyond resource extraction that despoils the land, poisons the air, pollutes the water, impoverishes the communities, and ultimately warms the planet. How this phase will unfold is still in the drafting stages, though the ebb and flow of power in Appalachian coalfields would indicate that it is once again time for workers and communities to be on the winning side of Appalachia’s enduring power struggles between humans and corporations.

This is not an isolated pattern in West Virginia, but rather it is one that we are seeing unfolding at all levels of organizing and politics in the United States. And with history as our guide, we can be certain that the future will not unfold toward community and worker justice without our participation, without our stories, and without our solidarity with workers and communities across the United States.

Works Cited

Blizzard, William. When Miner’s March. Ed. Wess Harris. Oakland: PM Press, 2010. Print.

Cash, Wiley. The Last Ballad. A Novel. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2017. Print.

Evans, Mari-Lynn, Jordan Freeman, Deborah Wallace, J D. McAteer, and Richard L. Trumka. Blood on the Mountain. , 2017.

Haught, James. “A short history of mining -- and its decline -- in West Virginia.” Beckley Register-Herald. 30 March 2017. 20 April 2022. <https://www.register-herald.com/opinion/columns/a-short-history-of-mining----and-its-decline----in/article_4c968cfd-8d8b-51c7-bccb-77e186ea61f7.html>

Williams, John Alexander. Appalachia: A History. Charlotte: University of North Carolina Press, 2002. Print

nice read! I'll have to check out the Last Ballad. I live in North Carolina